Pancreatic cancer is one of the deadliest foes in the world of oncology. With a five-year survival rate hovering around 10-12% for most patients, it’s often called a “silent killer” because symptoms appear late, and by then, the disease has usually spread. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the most common form, is particularly aggressive, fueled by mutations in genes like KRAS, which drive uncontrolled cell growth. For decades, treatments like chemotherapy have offered only modest extensions of life, with tumors quickly developing resistance. But now, a stunning study from Spain’s National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) offers a glimmer of hope: researchers have completely eliminated pancreatic tumors in mice using a novel triple-drug therapy, with no signs of relapse even months later.

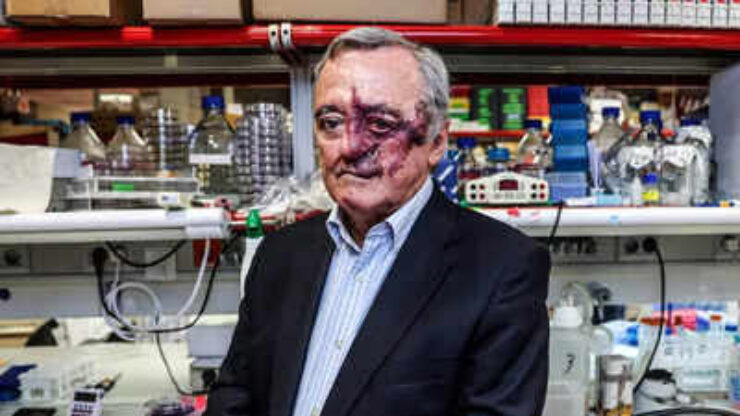

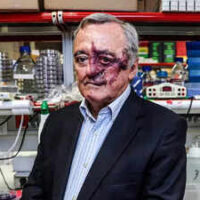

This isn’t just another incremental advance it’s a potential paradigm shift. Led by the renowned oncologist Mariano Barbacid, the team targeted the cancer’s adaptability head-on, combining drugs that shut down multiple survival pathways at once. The results, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), show that this approach could pave the way for more effective human treatments, though experts caution that mouse models are just the starting point.

To appreciate this breakthrough, it’s essential to understand why pancreatic cancer is such a tough adversary. The pancreas, a vital organ tucked behind the stomach, produces enzymes for digestion and hormones like insulin. When cancer strikes here, it often involves KRAS mutations, present in about 90% of PDAC cases. These mutations act like a stuck accelerator pedal, causing cells to proliferate wildly.

Tumors in the pancreas are also surrounded by a dense stroma a fibrous barrier that shields them from the immune system and makes drug delivery challenging. Standard treatments, such as gemcitabine chemotherapy, can slow growth but rarely cure, as cancer cells rewire their signaling pathways to evade attack. Single-drug targeted therapies, like new KRAS inhibitors, have shown promise in early trials but often fail due to this resistance. As Barbacid has noted, “Pancreatic cancer cannot be defeated with a single-drug strategy… the tumor is extraordinarily adaptable.”

Enter the CNIO team, who drew on over four decades of research into KRAS-driven cancers. Barbacid, a pioneer who helped identify the first human oncogene in the 1980s, has long focused on these mechanisms. Building on a 2019 study where they suppressed tumors in mice by eliminating EGFR and RAF1 proteins, the researchers identified a third key player: STAT3. This protein acts orthogonally (independently) to KRAS signaling, helping tumors survive even when other pathways are blocked.

The innovation lies in a carefully orchestrated combination of three drugs, each hitting a different vulnerability in the cancer’s machinery:

● Daraxonrasib (RMC-6236): A selective inhibitor of mutant KRAS, the primary driver of PDAC. Developed by Revolution Medicines, it’s already in clinical trials for human cancers and could gain approval by late 2026 or early 2027. This drug blocks the “downstream” effects of KRAS, starving the tumor of growth signals.

● Afatinib: An irreversible inhibitor of the EGFR/HER2 family of receptors, already approved for certain lung cancers. It targets “upstream” signals that feed into KRAS activation, preventing the tumor from bypassing the KRAS blockade.

● SD36: A proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) that selectively degrades STAT3, an orthogonal pathway that promotes inflammation and survival in cancer cells. This drug ensures the tumor can’t activate alternative escape routes.

By attacking downstream (via RAF1 equivalents), upstream (EGFR), and orthogonal (STAT3) pathways simultaneously, the therapy creates a “no-escape” scenario for the cancer cells. In essence, it’s like cutting off all the tumor’s lifelines at once, preventing the rewiring that leads to resistance.

The treatment was tested in multiple mouse models to mimic human disease as closely as possible:

● Orthotopic PDAC tumors: Tumors implanted directly into the pancreas, induced by KRAS/TP53 mutations (common in human PDAC).

● Genetically engineered mice: Animals bred to develop spontaneous pancreatic cancers.

● Patient-derived xenografts (PDX): Human tumor cells grafted into mice, preserving the genetic complexity of real patient cancers.

This multi-model approach strengthens the findings, as successes in one system might not translate to others.

Stunning Results: Tumors Vanish Without a Trace

In orthotopic models, genetic ablation (knocking out the genes for RAF1, EGFR, and STAT3) led to complete and permanent tumor regression. Translating this to drugs, the triple combination caused full tumor elimination in the majority of cases. In one experiment with 18 mice bearing human cancer cells, 16 remained disease-free for over 200 days post-treatment equivalent to nearly half a mouse’s lifespan with no relapse or metastasis.

Even in advanced tumors, the therapy induced significant shrinkage without regrowth. Importantly, the mice tolerated the drugs well, showing “unusually low toxicity” and minimal side effects, a critical factor for potential human use. Reviewers of the study praised the “durability of the response,” noting that such relapse-free outcomes are “exceptionally rare” in pancreatic cancer models.

Implications and Challenges During The Study

This study isn’t a human cure yet, but it’s a massive leap forward. By demonstrating that PDAC can be fully eradicated in sophisticated animal models, it challenges the notion that this cancer is inherently incurable. “We have a lot of work ahead of us,” Barbacid said, “but this is a huge step toward the real possibility of curing pancreatic cancer.”

Next steps include refining the therapy for other genetic variants, studying its effects on metastases (which cause most deaths), and identifying patient subgroups most likely to benefit. Collaborations with hospitals for fresh tumor samples will help bridge the gap to clinical trials. If all goes well, human testing could begin in the coming years, potentially combining this regimen with immunotherapy or other modalities.

However, caveats remain. Mice aren’t humans their biology differs, and tumors in people are more heterogeneous. Past breakthroughs in animals haven’t always translated, and scaling up drug production (especially for SD36, which is experimental) will be key. Funding is another hurdle; as Barbacid has pointed out, pancreatic cancer research often lags behind more “high-profile” diseases.

Still, independent experts are optimistic. The therapy’s low toxicity and broad applicability to KRAS-driven cancers (which include lung and colon types) could have ripple effects across oncology. As one recent analysis put it, this could “guide the development of new clinical trials that may benefit PDAC patients.”

In a world where pancreatic cancer claims over 500,000 lives annually, this Spanish-led discovery reignites hope. It’s a testament to persistent science: after six years of toil, Barbacid’s team has shown that even the toughest cancers might yield to clever, multi-pronged attacks. While we wait for human trials, one thing is clear the fight against this silent killer just got a powerful new weapon.

Reference

Published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS)