Key Findings

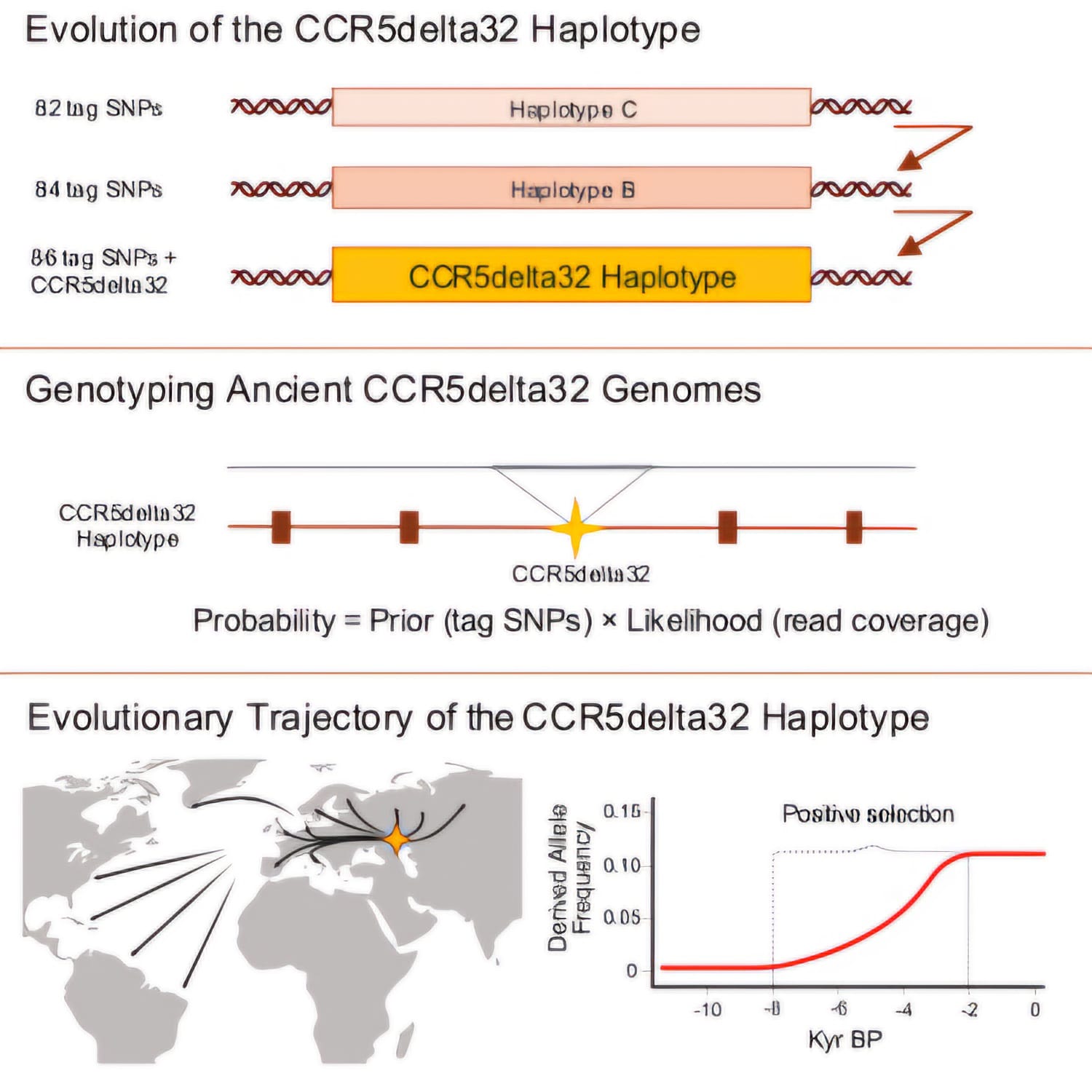

- The CCR5Δ32 genetic deletion emerged on an ancestral haplotype made up of 84 distinct genetic markers.

- This haplotype first appeared in populations of the Western Steppe around 6,700 years ago.

- The CCR5Δ32 variant experienced positive evolutionary pressure during the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age periods.

- These discoveries suggest a novel perspective on the medical significance of the CCR5Δ32 mutation.

Scientists have finally traced the HIV-resistant gene back to a single ancestor who lived near the Black Sea over 9,000 years ago. Modern HIV medicine is built on a ubiquitous genetic mutation. Today, researchers have deciphered where and when the mutation happened—and how it protected our ancestors from ancient diseases.

What links a thousand-year-old human from the Black Sea area to modern HIV medicine?

More information: Kirstine Ravn et al, Tracing the evolutionary history of the CCR5delta32 deletion via ancient and modern genomes, Cell (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.04.015

Plenty, it turns out, according to new University of Copenhagen research. The study is published in Cell.

About 18–25% of the Danish population carries a genetic mutation that makes them resistant or even immune to HIV. This knowledge is used to develop modern treatments for the virus.

Until now, nobody knew where, when, or why the mutation occurred. But with the use of sophisticated DNA technology, scientists have now solved this genetic puzzle.

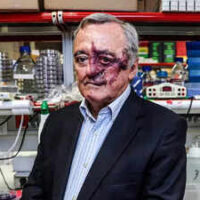

“It seems the variant arose in an individual who was living in a part of the world near the Black Sea approximately 6,700 to 9,000 years ago,” says Professor Simon Rasmussen from the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research (CBMR) at the University of Copenhagen, lead author of a new paper that tracks the mutation.

“HIV is a relatively newly emerged disease—less than 100 years old—so it’s almost accidental and extremely interesting that a change in the genes that occurred thousands of years ago also protects against a modern virus like HIV.”

To determine where and when the mutation first appeared, the scientists initially mapped it by examining the genetic code of 2,000 living people worldwide. They subsequently developed a novel AI-driven method to locate the mutation in ancient DNA on ancient bones.

The researchers compared information from over 900 skeletons dating from the early Stone Age to the Viking Age.

“By looking at this large dataset, we can determine where and when the mutation happened. For a period, the mutation is completely absent, but then it just pops up and spreads very quickly. If we combine that with our knowledge of human migration at the time, we can also determine where the mutation happened,” says first author Kirstine Ravn, senior researcher at CBMR.

So, the researchers were able to follow the mutation in a Black Sea dweller as far back as 9,000 years ago—a common ancestor from whom all mutation carriers descend.

But why did so many Danes inherit a thousand-year-old genetic mutation against a disease that didn’t yet exist?

The researchers believe that the mutation had appeared and evolved rapidly because it gave our ancestors an edge:

“This mutation had an advantage of surviving because it suppressed the immune system when humans were exposed to new pathogens,” says Leonardo Cobuccio, co-first author and postdoc at CBMR.

Kirstine Ravn add:

“Interestingly, the variation inactivates an immune gene. Sounds bad, but it likely was good. An overactive immune system can kill you—think allergic reactions or worst-case scenarios of viral infections like COVID-19, where the immune system likes to cause the damage that kills patients.”.

“As humans became less hunter-gatherer and more settled together in agricultural communities, infectious disease pressure increased, and a better-balanced immune system might have been advantageous.”

REFERENCE JOURNAL

More information: Kirstine Ravn et al, Tracing the evolutionary history of the CCR5delta32 deletion via ancient and modern genomes, Cell (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.04.015

Journal: Cell