Hey there, ever wonder what ancient flying reptiles ate?Turns out, our ideas about them just got a pretty wild update! For ages, paleontologists kind of assumed that pterosaurs—those fierce-looking, winged reptiles and almost all were meat-lovers. Researchers determined that these creatures primarily consumed fish, insects, and possibly other reptiles. This conclusion is backed by fossilized stomach contents from a genus known as Rhamphorhynchus, which consistently showed that its diet was primarily composed of fish.

But a discovery from China is flipping the script.

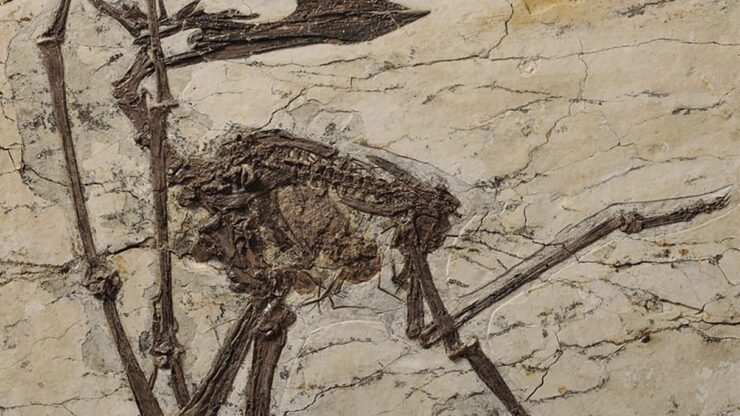

In northeastern China, around 120 million years ago, a pterosaur—specifically a species called Sinopterus atavismus—crash-landed into a shallow pond and died. What’s incredible is that this fossil didn’t just preserve its bones—it also kept its stomach contents intact. That’s a big deal. This is the first time scientists have ever gotten a glimpse inside the stomach of this kind of pterosaur.

Some scientists had guessed plant-eating might be possible…

Long before this fossil was discovered, some researchers began to question whether certain pterosaurs were exclusively carnivorous. They highlighted characteristics such as their beaks, particularly the toothless varieties found in a group known as tapejarids, which includes Sinopterus atavismus. These tapejarids had beaks shaped a lot like parrots’, perfect for chomping on fruit or cracking open nuts. But without hard proof, it remained a theory most paleontologists didn’t buy into.

This fossil of the pterosaur Sinopterus atavismus preserves the creature’s stomach, which contains hundreds of mineral deposits associated with plant matter—suggesting it died with a belly full of plants. Shunxing Jiang

Now, things have changed—because they’ve finally got the proof.

When researchers, including Xinjun Zhang and Shunxing Jiang, took a closer look at this particular Sinopterus atavismus specimen (a juvenile that was about 1.5 meters across—still small compared to the full-grown ones that could reach 2 to 4 meters), they used super high-resolution x-ray scans to peer inside. And what they found inside its stomach was completely unexpected.

Evidence one: quartz crystals that hint at tough diets.

Right at the top of its stomach, the team found a bunch of large quartz crystals. These kinds of stones are usually seen in animals that swallow gastroliths—stomach stones that help grind up food. Think of it like a built-in food processor. Today, many birds and lizards use these stones to help digest tough plant material, which means the pterosaur might’ve been doing the same thing.

Evidence two: phytoliths—tiny plant fingerprints.

Even deeper in the stomach, they spotted hundreds of phytoliths. These are microscopic mineral structures that form between plant cells. They’re like the fingerprints of the plant world, and finding them is like catching a plant in the act of being eaten. Before this, phytoliths had only ever been found twice in dinosaurs—once in fossilized poop, and once stuck to teeth—both times in clear herbivores. So finding them in a pterosaur’s belly? That’s basically a smoking gun that proves this pterosaur was munching on plants.

Even skeptics are changing their minds.

David Martill, a well-known paleontologist who wasn’t involved in the study, admitted the discovery completely changed his thinking. He used to believe those delicate beaks were made for snapping up tiny creatures like water fleas or insects. But this fossil proved otherwise. He even called it a “once-in-a-hundred-years discovery.”

The debate is finally settled.

This jaw-dropping discovery, recently published in Science Bulletin, is now considered strong enough to close the debate about whether pterosaurs ate plants. The answer? At least some of them absolutely did. And not just a bite here and there—they had full-on plant-based diets. This means scientists now have to reconsider how pterosaurs fit into ancient ecosystems. Were they seed-spreaders? Competitors to early herbivorous dinosaurs?

The plant clues point to woody favorites.

The types of phytoliths found in the pterosaur’s belly suggest it was mainly munching on woody plants, though there were traces of flowering plants and maybe conifers too. So these creatures may have had more sophisticated diets than anyone imagined, capable of handling tough vegetation just like some modern herbivores.

A discovery almost missed.

This remarkable story could have faded into history, but the exceptional preservation of this fossil, combined with the right tools and expertise, brought it to light. This discovery highlights the vast knowledge still to be gained from fossils and reveals that even the most intimidating creatures may have simply been enjoying a leafy salad.